Purchase Options

Buy this book for £9.99 post-free.

Buy this book if you live outside the UK (£14.00 postage included)

Any difficulties please contact:

Amolibros

Loundshay Manor Cottage

Preston Bowyer

Milverton

Somerset

TA4 1QF

Tel 01823 401527

Lucy Potter is a successful artist but she has done no new work in months. She fears she has lost the creative spark that sustained her and enabled her to express her view of the world. Will she ever regain it?

The chance discovery of an old notebook while on a walk in the woods provides a welcome distraction, raising questions she cannot answer. Who wrote it, why is it in code, what secrets does it hide? And why does it include the address of a house that does not exist?

Partial decoding of the notebook, surely written many years ago, reveals troubling incidents in the life of an unnamed girl. Deeply affected by the girl’s plight, Lucy feels impelled to find out who she is or was and what happened to her. Could she still be alive?

Lucy’s search for answers has an outcome she could never have anticipated. But will the re-appearance in Lucy’s life of fellow artist Rex Monday help or hinder her attempts to re-establish her position in the art world – and provide the stability she needs in her personal life?

As the story unfolds, we are drawn into the world as seen through Lucy’s eyes. A world of colour and light, of shape and pattern and texture, inviting us to see it that way too.

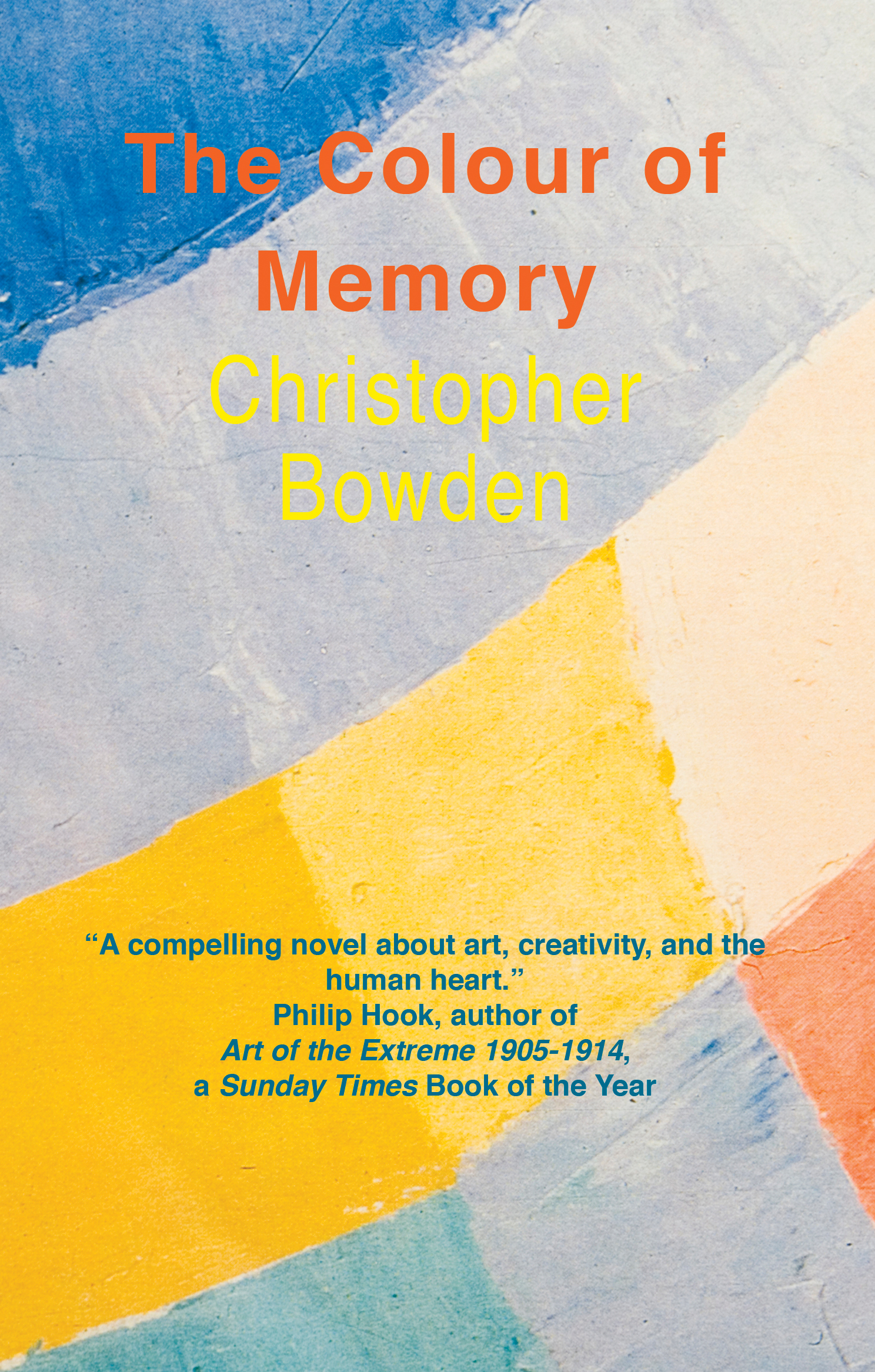

Of The Colour of Memory

‘A compelling novel about art, creativity, and the human heart.’

Philip Hook, author of Art of the Extreme 1905-1914,

a Sunday Times Book of the Year

Excerpts from The Colour of Memory

She had passed this way many times before and had no mind to linger now, her first thought being home, and the comforting embrace of an armchair in which she would almost certainly fall asleep. How much had she had? But sudden movement in a wide bay window snatched her attention. She found herself watching figures silhouetted against the light of lamps just switched on inside a room. And as she worked along the row of houses, she became aware of the colours and shapes of other lighted windows. Squares and oblongs and semi-circles of yellow and orange and gold, warm and welcoming yet excluding too, glimpses of lives of which she was not part. The outsider looking in.

Standing on the pavement in the half-light, she felt a keen sense of separation yet compelled to watch a series of vignettes: domestic scenes, unrehearsed performances on undersize stage sets, the window frame as proscenium arch and Lucy Potter an audience of one.

§

Lucy found herself telling Rosemary about her painting, its various phases, and her current efforts to overcome the block that had blighted the last few months. Rosemary, she reflected, had turned the tables but seemed genuinely interested. And building up some capital might be no bad thing, stand her in better stead.

“Windows, you say. Is that looking out or looking in?”

“Neither, really. It’s not about views through but the shapes and sizes of the windows themselves and the colours I choose to depict them.”

“Are we talking about real windows or imaginary ones?”

“Both. That’s to say, a real window may be the starting point for a particular painting but then my imagination takes over. So it ends up as something different.”

“No women gazing longingly from rooms they cannot leave? A caged bird in the background to rub the point in?”

“No,” said Lucy. “I don’t do people.”

“Any reason? I noticed that you didn’t mention portraits among your work.”

“I haven’t got the skill or the patience or the stamina. Think of all those sittings. And the pressure, the expectation that I would produce an acceptable likeness. Something that satisfied the sitter and anyone else who cared. I wouldn’t feel in control. Supposing they hated how I saw them, what I saw in them. If I revealed some inner qualities that clashed with the way they saw themselves or which they wanted to keep hidden. I’d have to be honest; I couldn’t flatter for the sake of an easy life. It’s too much of a risk for both parties. It’s easier to take liberties with places and things than with people.”

§

The path she took meandered between headstones starred with lichen and brought her to a porch on the south side, overseen by ancient yews that cast a pall even on this fine afternoon. Lucy hastened through the door into the body of the church. It was simple and unadorned; the large east window beyond the altar had nothing but plain glass. It was the smaller west window that made her catch her breath. Two Gothic lights and a quatrefoil above, the stained glass brilliant in the sun that struck the front, filling the walls and floor with radiance and colour. An abstract design of no obvious religious significance, as far as Lucy could tell. The varying shapes and hues gave the illusion of movement, of being alive.

Lucy was enchanted. She stepped into a pool of rose madder, shading to garnet red, before bathing in washes of orange and yellow and gold, and thence the richer tones of blue, indigo and violet. She wished she could have been there longer to see the light change through the day, move across the floor and walls, dissolving the shapes in its path.

§

Lucy left it for a while and then took a gamble. “The mirror in the kitchen corridor,” she said. “With the glass covered…”

“Well spotted,” said Rosemary. “It used to hang in the hall of the house in Buckinghamshire. I was fond of it, the ornateness of the frame, especially the birds and fruit and flowers entwined. And then she caught me looking at them, assumed I was admiring myself in the mirror. ‘Don’t waste your time, girl. No one’s going to look at you.’ I can still hear that sneering voice, see that face behind me reflected in the glass, criticising, judging.

“I eventually inherited the mirror and a few other things. It was put away for years, wrapped in blankets. But when Gordon died I retrieved the mirror from the attic and hung it where you see it now. Out of the way but not out of the way. Less need for explanations.”