Purchase Options

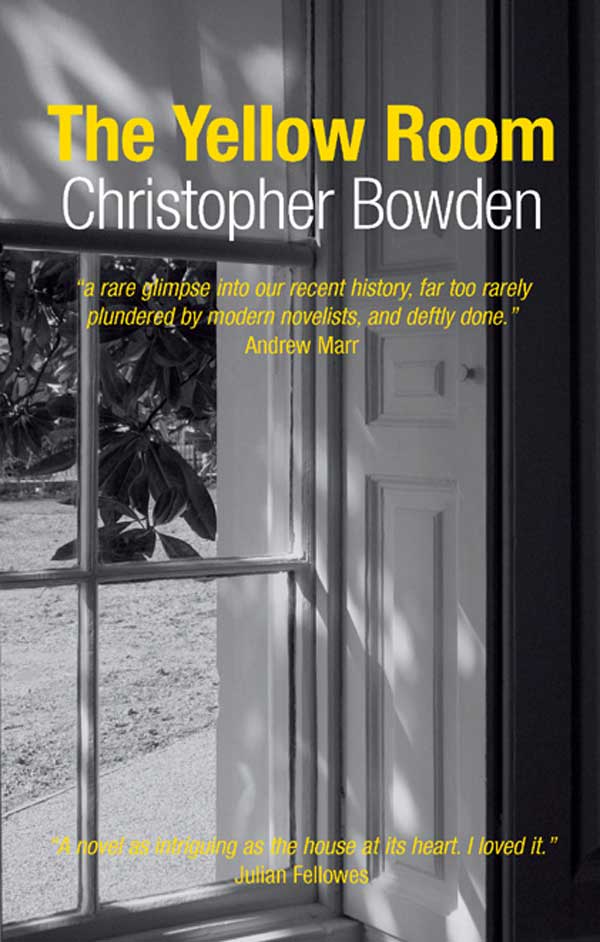

Buy in the UK for £8.99 post-free Buy overseas for £12.99 incl postageThe Yellow Room is Christopher Bowden’s second novel.

May Finch had lived in the Suffolk town of Nettlesham for fifty years, had never married and had brought up her daughter by herself. Why did she take pains to keep a guide to distant Brockley House? Why did she underline key parts of the guide? And what is the significance of two things slipped inside it?

Stumbling across the guide after May’s funeral, her granddaughter Jessica becomes intrigued by the place and the people and the unanswered questions. Bored by her job and empty private life, she decides to find out more, becoming ever more deeply drawn into the hidden past of an English country house and the family that lived there. A past that would change her future. Nothing would be the same again.

Centred on Brockley House, a Georgian mansion nestling in a Hampshire valley, the contemporary story is illuminated by flashbacks to the 1950s. This is a literary mystery delving into a recent past, taking the reader from a country house to Kenya at the time of the Mau Mau uprising; it makes a rich period piece.

Of The Yellow Rom

“…a rare glimpse into our recent history, far too rarely plundered by modern novelists, and deftly done.”

Andrew Marr

“A novel as intriguing as the house at its heart. I loved it.”

Julian Fellowes

“…quintessentially English…an intriguing book, full of family mysteries and deception.”

Oxford Times

Excerpts from The Yellow Room

She looked at her watch again, shifted in her chair and pulled at the ends of the dark brown hair falling from her shoulders. She leaned forward on the table and dragged the chair closer. It scraped horribly on the tiled floor. The desiccated couple at the next table glared over bags and packages and tutted in unison. Jessica reddened and reached for the saucer of sugar lumps. They were tightly wrapped in reproductions of Cubist paintings.

There’s no point in what ifs, she reflected, as she placed one lump on top of another. It had to be faced. What’s done is done and can’t be undone. The leaning tower of lumps wobbled dangerously. How much simpler if she had put back what she found in her grandmother’s cottage all those months ago, left things as they were, lying undisturbed. Brockley House would have remained a name unknown, a place unvisited, and she would have been none the wiser. But once she had set off down the road she needed to know where it led. And she wouldn’t have met Duncan, either, would she? That was worth all the rest put together. Where was he?

Anyway, she thought, problems were there to be solved. She did not like ambiguity, uncertainty, loose ends. Perhaps it was her legal training, or maybe she just had the kind of mind that made her want to be a lawyer in the first place. And no one had been hurt, had they? Not really. Not much. Not yet.

She coaxed the last remaining Braque onto a wayward Picasso. It was a lump too far. The tower collapsed, sending cubes in all directions. The desiccated couple collected their bags and packages and huffed up the stairs to the street above. A slim man with sandy hair brushed past and patiently gathered the errant lumps.

“Sorry, I’m late,” said Duncan Westwood, kissing Jessica warmly on the lips as she jumped up to meet him.

§

Margaret was still in the garden. She was talking business by the lupins with a man with a black moustache, a large gold ring and an unpleasantly knowing smile. Left to herself inside, Jessica crept up the wooden stairs, as quietly as they would allow. Flakes of whitewash from the walls were caught in cobweb beneath the banister rail. Through force of habit, she knocked softly on the door of May’s bedroom before going in. The room looked the same but felt different, empty, strangely still. She sat down slowly on the edge of her grand-mother’s bed.

It yielded with a gentle sigh. She looked at the familiar prints on the wall above: The Haywain, a Turner sunset, St Francis mobbed on the outskirts of Assisi by birds of uncertain species and improbable colour. With her left hand she traced the octagons of the patchwork quilt, pink and grey and powder blue. Her feet rumpled the rag rug on the bare floorboards. Bending down to straighten it, she saw that the door of the bedside cabinet was slightly ajar. Guiltily, she inched it open, as if a gradual breach made it less of an intrusion, less of an invasion of privacy. Somehow, it still mattered.

§

Twenty minutes later she was moving swiftly. She held her bag close against her. She felt guilty but exhilarated. It was pure impulse, done on the spur of the moment. She had seen her chance and taken it. Removing the bottle of water had created a bit more room. She had slipped it behind the chair vacated by the attendant, who had rushed next door to help his colleague restrain the badger-hunters hitting each other with their clipboards.

Her first instinct was to leave the House straightaway, to get clear as quickly as possible. But she had unfinished business. Pink and panting, she darted up the stone stairs between the Marble Hall and Dining Room. A large Gainsborough clung to the wall. It was his portrait of the Brockley sisters, Fanny and Lydia. One standing, the other sitting. Both with knowing looks and the ghost of a smile. As Jessica reached the landing outside the Chinese Bedroom, she hesitated, trying to decide which way to go. If she had turned round she might have seen the man with sandy hair consulting his guidebook at the bottom of the stairs. He had taken the taxi from the station and got to the House first, leaving his battered leather bag at the entrance.

She went into the Chinese Bedroom. A couple were inspecting the Kändler in the illuminated cabinets. She could see this was not right. She went back to the landing. There was a door marked PRIVATE, with a bell to one side above a chipped red fire extinguisher. This looked more like it. She tried the handle. The door was locked. To the right the stairs continued. Not the stone stairs with the elaborate iron balustrade but a simpler wooden affair with plain white banisters. A NO ENTRY sign swung gently on a chain at the bottom. She took off her sandals, picked them up and was over.