Purchase Options

Buy in the UK for £8.99 post-free Buy overseas for £12.99 incl postageThe Red House is Christopher Bowden’s third novel.

Her face was thinner than it used to be, tauter somehow, almost gaunt, and the eyes seemed troubled. The hair, once long and flowing, was cut roughly short. Almost hacked, he thought. Yet it was surely her…

When Colin Mallory sees a sketch of a young actress he once knew on display in the local market, memories of their past together are brought back sharply to the surface. Alarmed by her distressed appearance, Colin is propelled on a search that draws him into the nightmare world of ‘the group’ and the sinister influence that threatens to control him too.

This is an engrossing story of artifice and hidden secrets, rich with theatrical detail and a cast of compelling characters.

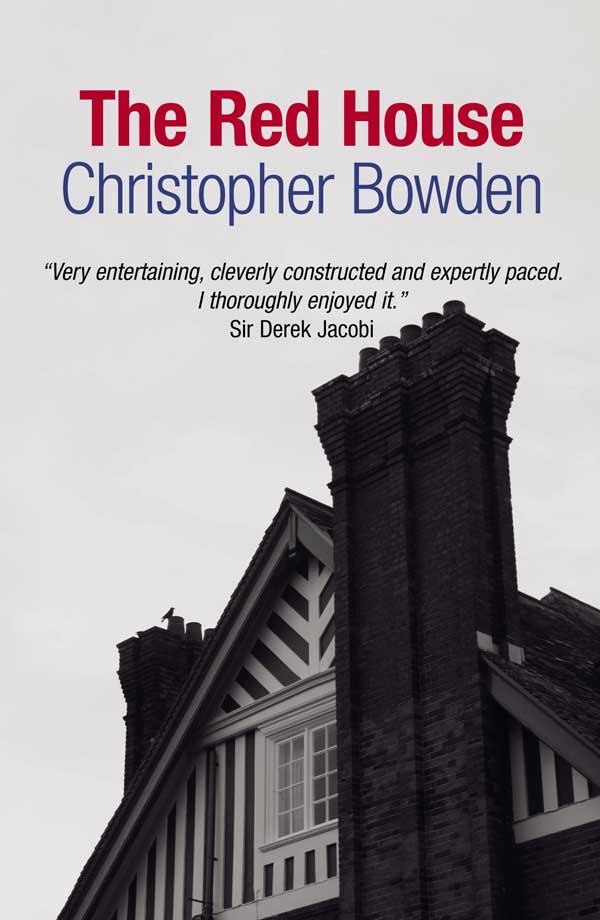

Of The Red House

“Very entertaining, cleverly constructed and expertly paced. I thoroughly enjoyed it.”

Sir Derek Jacobi

Excerpts from The Red House

“You have one new message. Message received today at four-fifteen pm.”

Blast. Less than ten minutes ago. He pressed one.

“It’s me, Col.” Bryony! But where, how…? “I tried to see you but they’ve taken me back.” Her voice was strained and shrill. “They don’t like people leaving. Sir says it’s disloyal.” She started talking faster. “I wasn’t good enough. That’s what they told me. They said I had to work harder until I got it right.” Then calmly she said, “I deserve to be punished. I know that. Tonight they will tell me in front of the others. I…” A squeal and the line went dead.

He listened to the message again and again and then once more. That voice, her voice, after all these years. Achingly familiar, disturbingly different. He pressed zero to return the call. It rang but there was no reply. He tried 1471. It was a mobile phone number. Nothing to indicate where she was. He wrote down the number and pressed three to return the call by that route. A gentle hiss, then silence.

His thoughts were racing: elated, concerned, confused. She was being held against her will. That much was clear. Why else had she tried to escape? But from what or whom? Some kind of group or sect, with this ‘Sir’ as its leader? How on earth had she got caught up in that? Her distress was all too evident. Yet there was an underlying matter-of-factness, an acceptance of whatever was in store for her that he found even more unsettling.

The Limelight entry gave her agent’s name and contact details. A bit old but worth a try. He rang the number.

“Bryony Hughes? Well may you ask. We’d very much like to know where she is ourselves. Never answers calls or correspondence. We’ve decided to take her off the books.”

The agent parted with Bryony’s own contact details without too much fuss but they plainly related to her old Peckham flat. She could hardly expect work to be put her way if she did not keep them up-to-date. Maybe that was the point: she was being held captive somewhere and could not keep her agent in touch. And yet she had been able to phone him, Colin, even if the call had been cut short.

He dredged from his memory a clutch of contemporaries from St George’s and struggled to recall where they had lived. The phone book yielded numbers but calls were no more productive. One had moved, one was abroad, a third had just got back from work but knew nothing of Bryony’s current whereabouts.

There was only one option left.

§

They sat at a table in the garden of the Sailor’s Retreat, a quiet pub on the corner of Victoria Road and Albert Terrace. Ken’s pint of Curate’s Winkle glowed amber in the late afternoon sun. Colin thought it prudent to stick to coffee. It was a long way back to Oxbourne in any case.

“He was never an actor of the first rank,” said Ken. “But he was a good second division player. A stalwart of weekly rep. Took over from Stamford Brook at Hornchurch for a while. That’s where I saw first saw him, as Abanazer in Aladdin, sometime in the early ‘sixties. Frightened the life out of me.”

“You were still at school?”

“I certainly was. Hadn’t yet taken my eleven plus.”

Colin looked blank.

“Anyway, he and Celerity B had a string of successes in the West End in totally forgettable plays. I used to see their pictures in Curtain Up! It was one of the theatre mags. Hasn’t existed for years.”

“And then?”

“He wangled a job as director at the late lamented Sanderling Rep. Tried to redeem his reputation as a serious actor with forays into the classics. Mostly vehicles for him and his good lady wife, if you ask me. Eventually, the Rep folded and it was downhill all the way. A few character parts. The odd bit of telly. Eventually, the phone stops ringing for good. Comes to us all, in the end.”

“So they retired round here?”

“Not a clue,” said Ken, with an affected shrug. “I expect they were passing through, like thousands of others with a craving for a shovelful of shellfish before their cream teas. They’re probably tucked up in a nursing home somewhere. I haven’t seen any obituaries.”

§

He woke early the following day. A soft peach-tinted glow had replaced the darkness of the night. Through the nearer dormer he surveyed the empty beach, shimmering orange-brown in the early morning sun. A Friday colour, he thought. In the sky, a scribble of cloud and a handful of seagulls, their raucous and insistent cries muted in deference to the hour.

He creaked downstairs after an invigorating shower. He felt almost human, despite the enforced recycling of yesterday’s clothes. A visit to an all-night chemist after his escape from the beige embrace of Ray and Flo had yielded toothpaste and other essentials.

There was no sign of life on the ground floor. The all-pervasive stench of stale beer made him feel slightly sick as he scrawled a note saying he was coming back for breakfast. He slipped it under the right arm of the bear he propped against the till in the public bar.

He let himself out carefully. The air was cold and clear. He took the board walk past quiet cottages, pink and white and forget-me-not blue. Tamarisk and rosemary spilled over paling at the front. Further on, larger houses with verandas, empty chairs, looking towards the sea. The board walk stopped abruptly. He crunched on through the shingle, not the uniform brown he had seen from the window of his room but resolved, close-at-hand, into its constituent parts. Rust and ochre, cream, charcoal and grey.

A regiment of beach huts, ranged on stilts, shuttered and still. Mobile homes huddled behind newly-planted holly hedges. Shingle gave way to coarse-grained sand. There, the traces of a fire in a gentle hollow, surrounded by lumps of blackened stone. It was still warm. He crouched and picked at the charred remains. A pencil, some cloth-covered buttons, scraps of lined yellow paper, as if torn from the sort of American legal pad he used to use himself. And a mask, blistered and scorched in places but otherwise free from damage. Made of papier mâché, and dotted with sequins, it sparkled purple and gold as he turned it in the sun. It would not have looked out of place at a Venetian masked ball. Pretty incongruous lying on an English beach, though. No doubt it was left over from a fancy dress party but why try to destroy it?

A track emerged from a field in which horses were grazing. It curved away from the beach and climbed towards an area of trees by which it was absorbed. Colin followed the sharp, flinty path past banks of bramble and thick grass until he came to a high wall topped by straggling pines. Patches of render had fallen to the ground here and there to reveal the orange-red brick beneath. He was too close to the wall to see what lay behind it.

The studded door set tightly between two piers had no handle or other visible means of opening. Yet the worn stone step spoke of years of coming and going. He pushed against the door. A harsh metallic click, then nothing. The door did not move at all.

The track wound through a small copse of oak and ash, the wall a constant presence between the trees. He caught glimpses of the ridge of a roof, a weather vane in the shape of a dragon, tall chimneys, some single, some grouped. He emerged by a pair of wide wooden gates, much the same height as the wall and crowned with spikes. To one side, a block of limestone with letters incised and picked out in reddish gold: KEMBLE PLACE. As he backed away from the gates, other features came into view: the top of a tower, a half-timbered gable, part of a window, tile-hung walls: components of a big house above the beach. This, surely, was the home of Howard Desmond and Celerity Box. No sign of life, no obvious way of slipping in quietly, but at least he knew where it was now. He would have to come back.