Purchase Options

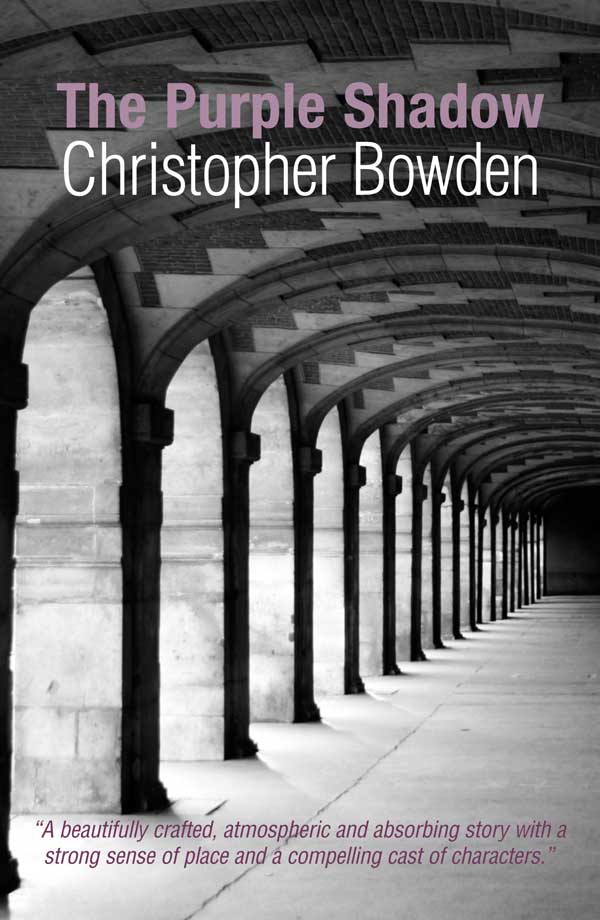

Buy in the UK for £8.99 post-free Buy overseas for £12.99 incl postageThe Purple Shadow is an atmospheric story with a strong sense of place, and is Christopher Bowden’s fifth novel.

In the years before the war, Sylvie Charlot was a leading light in Paris fashion with many friends among musicians, artists and writers. Now she is largely forgotten. Spending time in Paris during a break in his acting career, Colin Mallory sees a striking portrait of Sylvie. Some think it is a late work by Édouard Vuillard but there is no signature or documentary evidence to support this view.

The picture has some unusual qualities, not least the presence of a shadow of something that cannot be seen. Perhaps the picture was once larger. Colin feels an odd sense of connection with Sylvie, who seems to be looking at him, appealing to him, wanting to tell him something. Despite a warning not to pursue his interest in her portrait, he is determined to find out more about the painting, who painted it, and why it was hidden for many years.

Colin’s search takes him back to the film and theatre worlds of Paris and London in the 1930s – and to a house in present-day Sussex. As he uncovers the secrets of Sylvie’s past, her portrait seems to take on a life of its own.

Of The Purple Shadow

‘A beautifully crafted, atmospheric and absorbing story with a strong sense of place and a compelling cast of characters.’

‘A compelling read. You’re drawn into the narrative immediately by the vivid description of a startlingly captivating painting and, as a reader, you’re as invested in getting to the bottom of the mystery as the main character is. Bowden is a sharp observer and I loved his descriptions of Paris and London and Sussex and the people who live in both city and country. The novel also spends time describing the lives of jobbing actors and the British film industry in the 1930s. This may be fiction but you feel, as you read, that it comes from a place of knowledge.’

The Bookbag

‘Full of idiosyncratic touches and descriptions, this is a story that will keep you guessing.’

France magazine

‘Christopher Bowden has again created an intriguing, literary tale with a well-drawn cast of characters. Actor Colin Mallory from The Red House can’t help but investigate a mysterious painting. The descriptive quality of the writing takes you to the back streets of Paris, and lets you really feel you are solving the mystery hand in hand with Colin.’

Lovereading

Excerpts from The Purple Shadow

The rue du Chardonneret was a narrow street of seventeenth-century houses. A little austere and forbidding at first sight but, as Colin pointed out to Paul in the dwindling daylight, the pallid stonework was enlivened – his word – by balconies, rustication and elaborate carving. Madame Ducasse had an apartment at number nine. The entrance to the building was set in an archway, topped by a classical pediment. She buzzed them through high double-doors that gave onto a cobbled courtyard. A staircase to the right wound up to the first floor and the warm rectangle of light that framed Madame Ducasse. Her hair shone yellow-gold.

“Please. Call me Marion.”

She led them to a comfortable sitting room with tall windows that faced the street and the small park opposite. While she headed to the kitchen and her unseen assistant, Colin and Paul roamed with white wine and canapés, looking at pictures, furniture, ornaments. Etchings by Matisse and Picasso vied with caricatures by Gillray and Daumier and some Sonia Delaunay fabric designs, Braque engravings were nudging a still life by Chardin, a pair of Oriental vases flanked a Giacometti stick man. All this and much more identified by Paul, who declared the eclectic arrangement inspired. Colin found it hard to take in; he sank to a chair and stared at the painting above the marble fireplace.

It was the portrait of a woman in her mid-twenties, perhaps. He guessed from her dress, the style of her hair, that it was painted in the 1930s. She too was sitting in a chair in front of a fireplace, hands loosely knitted in her lap, a ring glinting on one finger. She was looking directly at him with a knowing smile and a hint of complicity. Or so it seemed. The effect was disconcerting.

“Paul. Have you seen this one?”

“Good Lord,” he said, negotiating his way between two tables shaped like kidneys, “it looks like a late Vuillard, though smaller than others I’ve come across.”

“Late who?”

“Vuillard. Édouard Vuillard. Probably best known for interiors and domestic scenes. He focussed mainly on portraits in his last twenty years or so. He died during the war.”

§

He brushed the crumbs from his trousers and removed the book from his bag. Then he remembered the message on his phone. Paul had printed the photographs of the painting and crawled over them – at length and in detail, apparently. He had not found a signature but still thought it could be a late work by Vuillard. He’d had no more luck than Madame Ducasse in finding any mention in the reference books or on-line. He would ask around and let Colin know how he got on.

Sylvie herself was enjoying the attention, Paul said. Her smile seemed to have become broader, her expression more knowing, almost mischievous, as if she were playing a game. And that shadow on the rug. In close-up, the purple fragmented, broke down into small dots of colour of varying intensity so that the shadow was more subtly modulated than at first appeared. The only thing was, its position in the photographs wasn’t quite as he remembered from the painting; the shadow seemed a slightly different size and shape and a bit closer to Sylvie. But he couldn’t be sure and he’d look at the photographs again in a few days.

§

He turned to Charles Kent. Of Meet Me in Margate and How Many Sailors? the less said the better, declared the author of the article Colin had found. However, it seemed that the actor went on to achieve some celebrity in a series of thrillers of the late 1930s and early 1940s. The author singled out for particular praise Murder in the Marshes, Crime Before Midnight and No Harm in Asking, in which Charles had appeared as amateur detective Rex Strong, a role he reprised in his final film Danger in Dorking.

Final film? Charles was killed in an air raid in 1943. A photograph showed him well-groomed and charming in the part of Rex, dashing even, with just a hint of the devilish. The article was sketchy about his earlier acting career, saying little more than that he had been classically trained and had played a number of Shakespearean roles ‘in this country and abroad’. Nothing about Paris, Lysander or the Arden Players.

Colin sat back and looked in the direction of the quai de Valmy, the canal beyond. He felt curiously upset by a life cut short, a career unfulfilled. A small dog snuffled at his feet, rootled under the bench for a few moments and trotted on its way. A sudden gust propelled a newspaper along the path and wrapped it round the base of a fountain. He picked up his phone and flicked between the costume designs for Demetrius and Lysander. The contrast with Uncle Arthur was painful. Was this what his own career held in store? Perhaps he should get an agent rather than rely on personal contacts and occasional searches for auditions and castings.

As he switched from one set of designs to the other, he noticed that Charles’ name was consistently underlined, whereas Wallace’s was not. And those for Lysander had marks, possibly initials, in the bottom right-hand corner. Who was the designer? He had only looked at the cast. He scrolled through the programme and found the answer. Sets and costumes by Sylvie Charlot.

§

He drifted along trestle tables piled with bric-a-brac, a bizarre mix of the mundane and the quirky – plates and bowls, ashtrays and cups, soapstone figures and African masks, a bust of Napoleon III painted pink, fans that had seen better days, a collection of china cats and dogs, lamps with shades and lamps without. A box of LPs – mostly French artists unknown to him – nestled between two tables; behind, piles of comics and magazines that he could not be bothered to look through. He picked up a glass fish, thought of Dr Trivau, and put it back.

He came to a stall more ordered than most. It was under an awning and devoted to books. They were laid out on a dark green cloth in rows too neat to disturb. The stallholder, a studious-looking man with gold-rimmed glasses, acknowledged him from his perch behind the table and went back to his paper. A run of books bound in leather and tooled in gold: Balzac, Stendhal, Victor Hugo, Saint-Simon, Chateaubriand; a clutch on geology, natural history and topography; oversize volumes on art and architecture; some handsome illustrated books on the theatre that he dared not touch and knew he could not afford.

The man nodded towards the boxes at the end. They had once held bananas but now contained a mixture of books in English, German and Spanish. The English ones were mainly American crime interspersed with a few old Penguins. He flicked through them and pulled out a couple by P G Wodehouse. In the gap that was left, Colin saw the bright yellow boards of another book lying on its side. He eased it out and read the title: Paris Days, Paris Nights: Memories of a city between two world wars. The author was Eve Maxwell. The book was tight, the pages crisp and decorated with details of Paris street scenes drawn by the author herself. It had been published in New York in 1948.

The man took five euros for the three. Colin put them in his bag and went in search of coffee before heading towards the avenue Daumesnil to tackle the Promenade Plantée.