Purchase Options

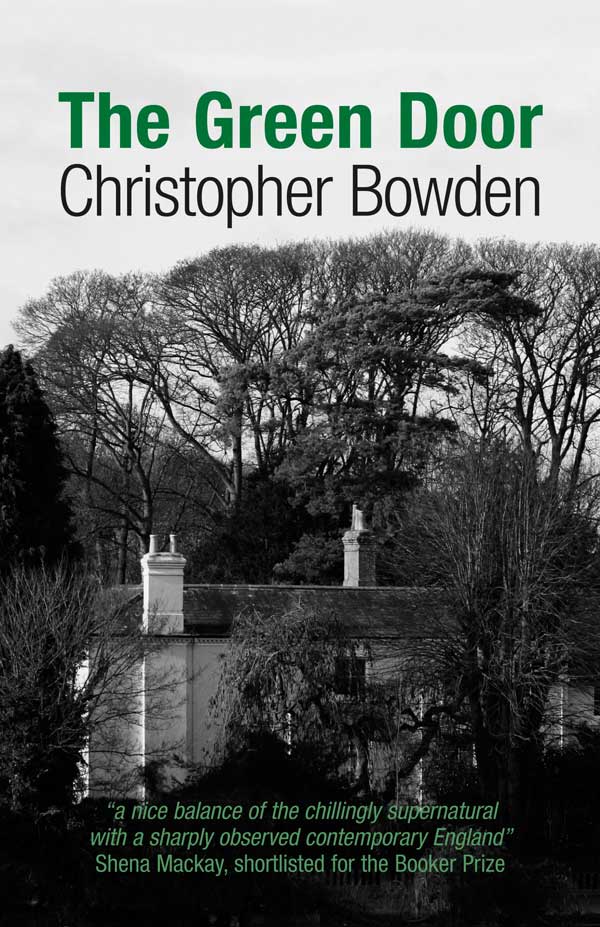

Buy in the UK for £8.99 post-free Buy overseas for £12.99 incl postageThe Green Door is a is a ghost story and a literary mystery, and is Christopher Bowden’s fourth novel.

BEATRICE NEWTON

1876 – 1887

She fell asleep too soon

Clare Mallory has a Victorian mourning locket with the photograph of a girl and a curl of her hair. When Clare loses the locket in a fortune-teller’s tent her quest to find it draws her into a dark episode of the family’s past and the true circumstances of the girl’s untimely death at Danby Hall, her Norfolk home.

The locket has been taken by the fortune-teller herself, sensing a troubled history and danger ahead. But her attempts to understand the warning signs release forces long held at bay. Events of the past seep into the present until the reappearance of a man who vanished from Danby Hall in 1887 threatens not only her life but Clare’s too.

Of The Green Door

‘Draws the reader in immediately and has all the elements of an intriguing mystery. In short, a page-turner. The heroine, Clare, is engaging and Madame Pavonia a suitably exotic yet credibly mundane fortune teller, and throughout there is a nice balance of the chillingly supernatural with a sharply observed contemporary England peopled by vividly painted characters…some lovely idiosyncratic touches and descriptions.’

Shena Mackay, shortlisted for the Booker Prize.

‘Subtly written but still a page-turner, it is a spine-chillingly enjoyable read.’

The Lady

‘…strange but appealing…’

Herald Scotland

‘…an interesting and unusual story. I enjoyed the blend of mystery and supernatural. It’s quite the page-turner but it doesn’t neglect character and detail. Absorbing and evocative, The Green Door is a truly enjoyable read.’

The Bookbag

Excerpts from The Green Door

It was on this large oak table that Clare placed a small card shortly after the taxi had delivered her safely to the gate of number twelve. Not the card the driver had given her in lieu of a proper receipt but the one she had found on the mat next to the bill that represented that day’s post. She lined it up with the others. Five of them now, each a different colour but all saying the same thing in gilt letters: ‘MADAME PAVONIA. Clairvoyant. Your future told, your problems solved.’ No contact details, no other information to suggest how anyone could avail themselves of Madame Pavonia’s services. Even if they wanted to.

The latest one was blue, following on from red, orange, yellow and green. Five days, five cards, five colours. A rainbow sequence, thought Clare, but incomplete. Were there two more to come? Then what? They were well produced but why go to the trouble and expense of printing them and pushing them through letter boxes without revealing where Madame Pavonia was based or how to get in touch with her? Perhaps, she reflected, it was the start of a wider campaign or was softening people up for personal visits.

Anyway, what problems did she want solved? She didn’t have time for problems.

§

“How may I help you? Have you suffered a loss or bereavement? Do you wish to make contact with a departed? Or do you seek guidance in matters of love or the direction of your life?”

“Er, nothing specific. Just curious, really. I saw your cards and your name on a flyer.”

“Ah, yes. Let us see what counsel we may give you. But first I fear we must attend to the money side. I find it best to deal with this before a reading; it is so easy to forget by the time we have finished.”

Disposing discreetly of the ten pound note, Madame Pavonia asked Clare to put her hands on the table, close to the crystal but taking care not to touch it. The fortune-teller shut her eyes and appeared to relax, breathing slowly and evenly. Her lips moved but no sound emerged. Was she in a trance? Gradually, she unclosed her eyes and gazed into the ball. Clare noticed it had minor cracks and imperfections. They caught the light of the candle and sparkled.

“I see the number one. Perhaps you are alone or too self-reliant. I see a well. It runs deep. You keep your feelings hidden or reserved for someone or something important. I see a ship or a boat. It is capsizing. This could mean a failure to communicate with a person in the past.”

Madame Pavonia looked more deeply into the ball and frowned.

“I see a tower: you feel trapped or imprisoned in some way, maybe in a job or a way of life. There is a bridge. It offers an opportunity, but use it wisely. Once that path is taken, there is no going back. Yet there is a barrier, a wall, an obstacle that must be overcome before progress can be made. Or perhaps it is some resistance on your part. I see the letter P…and a hand outstretched. This could be someone you know who wants to help you. Even if you do not yet realise it. Even if you do not think you need such help.

“Does any of this make sense to you, my dear, provide some pointers that may assist you in life’s journey? If you have any questions, do feel free to ask me.”

Clare stared for a while into the flame of the candle, guttering, sputtering its last. Madame Pavonia leaned back in her chair on the other side of the table and coughed gently. Then Clare said, “Thanks but it’s rather all-purpose, isn’t it? A bit indefinite. I mean, it could apply to pretty well anyone. To a greater or lesser extent. And are we talking past, present or future?”

“Life is a continuum. The future becomes the past soon enough. The present is barely the blink of an eye.”

“The board outside says you reveal people’s futures.”

“I see their futures, as a rule. Sometimes it’s best not to reveal all that I see. People are looking for a positive outcome.”

“And in my case?”

“The crystal remained cloudy. Whatever was there was obscured.” Madame Pavonia faltered. “There is nothing I can add.”

“What do you mean?”

“My dear, I saw no future.”

§

She looked across to the rows of headstones, pallid and pockmarked, set like giant teeth in new-mown grass. Unused the churchyard may be but at least it is neatly kept. She wondered how to find where Beatrice was buried. The guide said that many of the late Victorian graves were concentrated towards the eastern end ‘but that is by no means an invariable rule’.

The optimism she had felt when the taxi dropped her by the lych gate was beginning to wane. Why had she thought the task would be straightforward? She left the gravel and took the grass path that led towards the yews at the far wall. The crenelated tower of flint and clunch was behind her as she moved roughly parallel to the long low nave and chancel.

She worked methodically among the stones, weathered and worn and scarred by lichen. Names and dates were barely legible. A cluster from the 1880s raised her hopes but yielded nothing. She steadied herself against the memorial to one Emily Brandon that rose beside her and gulped water from the bottle she pulled from her bag. Where to go next? She was tempted to ask the man she had seen from the corner of her eye standing by the rain barrel at the end of the church whether there was a map or plan or some other record of people buried here. He looked as though he tended the place, judging by his clothes and the sickle in his hand. Yet when she turned round he was no longer there. The churchyard was deserted.

She had to get out of the sun. The yews offered shade and she made towards them. It was pleasantly cool under the trees. But as she approached the wrought-iron bench on which she had intended to sit for a while the air became chill, deathly cold. Nettles and long grass lay scattered on the ground, hacked rather than cut and recently by the look of them. They had not even begun to wilt. Then she saw it: protruding from the severed stalks, a small grave, better preserved than most.

Clare knelt, rubbing the goose bumps on her arms, and read,

BEATRICE NEWTON

1876 – 1887

She fell asleep too soon.

Beneath the words, the image of a dove, carved into the stone.

She tidied the grave as best she could, wrapping a handkerchief round her hand to avoid being stung, and took some pictures on her phone. A resentful toad left the scene and loped towards a patch of dock.

§

“The room where the papers were found,” he said. “We think it may have been the one occupied in the Newtons’ day by the governess, Miss Jeavons. Ruth Jeavons, according to my researches. It has a connecting door to a smaller room, possibly the bedroom of the youngest child, Beatrice. We sometimes open up the two and use it as a suite for families.”

“She was only eleven when she died, Beatrice. One of those Victorian diseases, I suppose.”

“The records say ‘consumption’ or tuberculosis, as we would call it now. But there’s some suggestion that, even if she was ill, it was not the cause of the poor girl’s death.”

“What makes you say that?”

“Conversations with older residents of Great Danby when I first started looking into the history of the house some years ago. Well before their time, of course, but there were hints, rumours of something more violent. It must have been hushed up for some reason; there’s nothing in the newspapers of the period that I could find and no mention anywhere of a post mortem or an inquest.”

“No police involvement?”

“Apparently not. The family were, I believe, close friends of the local doctor.”

“Who signed the death certificate.”

“I imagine so.”

“None of which explains what actually happened. And the family left the house.”

“Shortly after Beatrice’s funeral. They went to London.”

“What happened to Miss Jeavons?”

“I don’t know. She seems to have disappeared without trace. I doubt she was local. The rest of the staff would probably have come from round here and may well have stayed in the area.”

Valentine drained his cup and said, “Apart from the gardener, Pollard. He left the village to work as head gardener at a house in Yorkshire and never came back. We know this from Harriet Rushton’s Rural Reflections, published in the 1930s. She was daughter of the rector here in the 1880s – we had one to ourselves in those days. Pollard was supposed to help with the Golden Jubilee celebrations she was organising but departed without a word before the big day.”

“When was this?”

“June 1887. The Jubilee was on the twentieth.”